TLDR

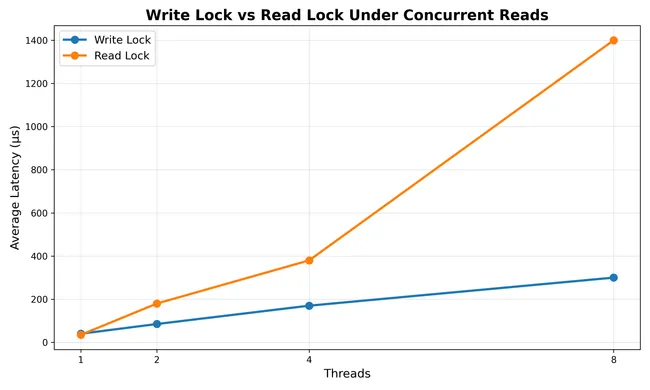

On commercial hardware, RwLock was ~5× slower than Mutex for a read-heavy cache workload due to atomic contention and cache-line ping-pong.

Introduction

This is a story about how “obvious” optimizations can backfire.

While building Redstone, a high-performance Tensor Cache in Rust, I hit a wall with write-lock contention.I thought a read lock would probably mitigate this (boy, was I wrong :( ). I expected the throughput to go through the roof since multiple threads could finally read simultaneously, the competition was not even close, write locks outperformed read locks by around 5X.

Here is why read locks may perform worse (and destroy expectations).

System Context & Workload

The experiment was simple: I was benchmarking a Least Recently Used (LRU) tensor cache.

- Hardware: Apple Silicon M4 (10 cores, 16GB RAM).

- Software: Rust 1.92.0, using the

parking_lot::RwLock. - The Goal: Maximize the throughput of the

.get()operation.

In a standard LRU cache, a get isn’t strictly a “read.” You have to update the internal state, to mark an item as recently used. However, I wanted to see if I could improve throughput by treating the lookup as a read and approximating the internal mutation.

The Conventional Wisdom

If you follow the standard documentation, the logic is sound:

- Write Lock (

.write()): Exclusive access. Only one thread moves at a time. - Read Lock (

.read()): Shared access. Multiple threads have access.

In a read-heavy tensor workload, the RwLock should be a massive win. But on modern multi-core chips like the M4, the “cost of admission” for a Read Lock is much higher than you think.

Benchmarks

pub fn get_with_write(&self, key: &str) -> Option<Arc<Tensor>> {

let mut inner = self.inner.write();

inner.get(key)

}

pub fn get_with_read(&self, key: &str) -> Option<Arc<Tensor>> {

let inner = self.inner.read();

if let Some((tensor, _, _)) = inner.map.get(key) {

Some(tensor.clone())

} else {

None

}

}

Why This Happened: The Hardware Reality

The culprit is a phenomenon known as Cache Line Ping-Pong.

1. The write hidden in plain sight (under a lot of documentation)

Even though you are calling .read(), you are performing a write operation at the hardware level. To track how many readers are currently holding the lock, parking_lot (and every other RwLock implementation) must increment an internal atomic counter.

2. The cost of invalidating

Modern CPUs move data in 64-byte chunks called Cache Lines. When Core 1 wants to increment the reader count, it must take “Exclusive” ownership of the cache line containing that counter.

When Core 2 tries to read the lock a nanosecond later:

- Core 1 must flush its change to the L3 cache/RAM.

- Core 2 must fetch that cache line across the internal bus.

- Core 2 marks the line as “Modified” to increment its count, invalidating Core 1s copy.

3. The performance Death Spiral

In an extremely fast operation like a cache lookup, your threads spend more time fighting for ownership of the reader-count variable than they do actually looking up tensors. The cache line pings/bounces back and forth between cores so rapidly that the CPU’s memory bus becomes a bottleneck.

The Paradox: A Write Lock is actually less noisy on the hardware bus because it prevents the stampede of cores trying to modify the same atomic counter at the same time. It instead gives control to only a single thread, which performs its intended operation,modifies internal state and gives the lock up.

The Lesson

- Beware of Short Critical Sections: If your work inside a lock takes only a few nanoseconds (like a Hashmap lookup), the overhead of an

RwLockwill almost always outweigh the benefits of concurrency. - Profile the Hardware: Use tools like

perforcargo-flamegraph. If you see a lot of time spent inatomic_add, you have cache contention. - Consider Sharding: Consider splitting your one giant cache into multiple buckets so that each holds a specific set of keys and has its own locking mechanisms, this will reduce the number of threads contending for the lock, it may also increase throughput since the number of truly parallel operations increases.

Read locks are not all bad and evil, there are a bunch of cases in which they prove to be much better:

- When you have larger sections in the read path that need to be under a lock, in this case write locks may slow down throughput.

- Writes are rare, then reads must be what you optimize for, but just remember to check how large reads actually are, in case of extremely small reads (order of nanoseconds) , you would probably be better off having a

Mutex, or a simpler locking implementation due to the same reason as above.

Conclusion

When using a locking strategy know what you plan to use it for, what the usage patterns are like, and always profile your code, it helps to bring weird cases like this to notice.